- Home

- Mosab Hassan Yousef

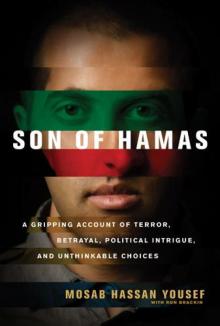

Son of Hamas Page 15

Son of Hamas Read online

Page 15

USAID was actually more than just a cover for me. The men and women who worked there became my friends. I knew that God had given me this job. It was USAID’s policy not to employ anyone who was politically active, much less someone whose father led a major terrorist organization. But for some reason my boss decided to keep me. His kindness would soon pay off in ways he would never know.

Because of the intifada, the U.S. government allowed its employees to enter the West Bank only for the day and only to work. But that meant they had to pass through dangerous checkpoints. They actually would have been safer living in the West Bank than running the gauntlet of checkpoints every day and driving the streets in 4 x 4 American jeeps with yellow Israeli tags on them. The average Palestinian didn’t distinguish between those who had come to help and those who had come to kill.

The IDF always warned USAID to evacuate if it was planning an operation that would put them in danger, but the Shin Bet didn’t issue such warnings. After all, we were all about secrecy. If we heard that a fugitive was headed to Ramallah from Jenin, for example, we launched an operation without forewarning.

Ramallah was a small city. During these operations, security troops rushed in from every direction. People barricaded the streets with cars and trucks and set fire to tires. Black smoke choked the air. Crouched gunmen ran from cover to cover, shooting whatever was in their paths. Young men threw rocks. Children cried in the streets. Ambulance sirens mingled with screams of women and the crack of small-arms fire.

Not long after I started working for USAID, Loai told me the security forces would be coming into Ramallah the following day. I called my American manager and warned him not to come to town and to tell everyone else to stay home. I said I couldn’t tell him how I had gotten this information, but I encouraged him to trust me. He did. He probably figured I had inside information because I was the son of Hassan Yousef.

The next day, Ramallah was ablaze. People were running through the streets, shooting everything in sight. Cars burned along the side of the road and shop windows were broken, leaving the stores vulnerable to bandits and looters. After my boss saw the news, he told me, “Please, Mosab, whenever something like that is going to happen again, let me know.”

“Okay,” I said, “on one condition: You don’t ask any questions. If I say don’t come, just don’t come.”

Chapter Nineteen

SHOES

2001

The Second Intifada seemed to roll on and on without even pausing to catch its breath. On March 28, 2001, a suicide bomber killed two teenagers at a gas station. On April 22, a bomber killed one person and himself and wounded about fifty at a bus stop. On May 18, five civilians were killed and more than one hundred wounded by a suicide bomber outside a shopping mall in Netanya.

And then on June 1, at 11:26 p.m., a group of teenagers were standing in line, talking and laughing and horsing around, eager to enter a popular Tel Aviv disco known as the Dolphi. Most of the kids were from the former Soviet Union, their parents recent émigrés. Saeed Hotari stood in line, too, but he was Palestinian and a little older. He was wrapped in explosives and metal fragments.

The newspapers didn’t call the Dolphinarium attack a suicide bombing. They called it a massacre. Scores of kids were ripped apart by ball bearings and the sheer force of the blast. Casualties were high: 21 died; 132 were wounded.

No suicide bomber had ever killed so many people in a single attack. Hotari’s neighbors in the West Bank congratulated his father. “I hope that my other three sons will do the same,” Mr. Hotari told an interviewer. “I would like all members of my family, all the relatives, to die for my nation and my homeland.”[7]

Israel was more determined than ever to cut off the head of the snake. It should have learned by then, however, that if imprisoning faction leaders did nothing to stop the bloodshed, assassinating them was unlikely to work either.

Jamal Mansour was a journalist, and like my father, was one of the seven founders of Hamas. He was one of my father’s closest friends. They had been exiled together in south Lebanon. They talked and laughed on the phone nearly every day. He was also the chief advocate of suicide bombings. In a January interview with Newsweek, he defended the killing of unarmed civilians and praised the bombers.

On Tuesday, July 31, after a tip from a collaborator, a pair of Apache helicopter gunships approached Mansour’s media offices in Nablus. They fired three laser-guided missiles through the window of his second-floor office. Mansour, Hamas leader Jamal Salim, and six other Palestinians were incinerated by the blasts. Two of the victims were children, aged eight and ten, who had been waiting to see the doctor on the floor below. Both were crushed beneath the rubble.

This seemed crazy. I called Loai.

“What in the world is going on? Are you sure those guys were involved in suicide bombings? I know they supported the attacks, but they were in the political wing of Hamas with my father, not the military wing.”

“Yes. We have intelligence that Mansour and Salim were directly involved in the Dolphinarium massacre. They have blood on their hands. We had to do this.”

What could I do? Argue with him? Tell him he didn’t have the right information? It suddenly dawned on me that the Israeli government must also be determined to assassinate my father. Even if he hadn’t organized the suicide bombings, he was still guilty by association. Besides, he had information that could have saved lives, and he withheld it. He had influence, but he didn’t use it. He could have tried to stop the killing, but he didn’t. He supported the movement and encouraged its members to continue their opposition until the Israelis were forced to withdraw. In the eyes of the Israeli government, he, too, was a terrorist.

With all my Bible reading, I was now comparing my father’s actions with the teachings of Jesus, not those found in the Qur’an. He was looking less and less like a hero to me, and it broke my heart. I wanted to tell him what I was learning, but I knew he would not listen. And if those in Jerusalem had their way, my father would never get the opportunity to see how Islam had led him down the wrong path.

I consoled myself with the knowledge that my father would be safe at least for a while because of my connection with the Shin Bet. They wanted him alive as much as I did—for very different reasons, of course. He was their main source of inside information regarding Hamas activities. Of course, I couldn’t explain that to him, and even the Shin Bet’s protection could end up being dangerous to him. After all, it would seem pretty suspicious if all the other Hamas leaders were forced into hiding while my father was allowed to walk freely down the street. I needed to at least go through the motions of protecting him. I immediately went to his office and pointed out that what had just happened to Mansour could just as easily have happened to him.

“Get rid of everybody. Get rid of your bodyguards. Close the office. Don’t come here again.”

His response was as I expected.

“I’ll be okay, Mosab. We’ll put steel over the windows.”

“Are you crazy? Get out of here now! Their missiles go through tanks and buildings, and you think you’re going to be protected by a sheet of metal? If you could seal the windows, they would come through the ceiling. Come on; let’s go!”

I couldn’t really blame him for resisting. He was a religious leader and a politician, not a soldier. He had no clue about the army or about assassinations. He didn’t know all that I knew. He finally agreed to leave with me, though I knew he wasn’t happy about it.

But I was not the only one who came to the conclusion that Mansour’s old friend, Hassan Yousef, would logically be the next target. When we walked down the street, it seemed that everyone around us looked worried. They quickened their pace and glanced anxiously at the sky as they tried to move away from us as quickly as possible. I knew that, like me, they were listening closely for the chug of incoming helicopters. Nobody wanted to end up as collateral damage.

I drove my father to the City Inn Hotel and told him to stay there.

“Okay, this guy here at the desk is going to change your room every five hours. Just listen to him. Don’t bring anybody to your room. Don’t call anyone but me, and don’t leave this place. Here’s a safe phone.”

As soon as I left, I told the Shin Bet where he was.

“Okay, good. Keep him there, out of trouble.”

To do that, I had to know where he was every moment. I had to know every breath he took. I got rid of all his bodyguards. I couldn’t trust them. I needed my father to rely on me totally. If he didn’t, he would almost certainly make a mistake that would cost him his life. I became his aide, bodyguard, and gatekeeper. I arranged for all of his needs. I kept an eye on everything that happened anywhere near the hotel. I was his contact with the outside world, and I was the outside world’s contact with him. This new role carried the added benefit of keeping me entirely free from suspicion of being a spy.

I started acting the part of a Hamas leader. I carried an M16, which identified me as a man with means, connections, and authority. In those days, such weapons were in big demand and short supply (my assault rifle went for ten thousand dollars). And I traded heavily on my relationship to Sheikh Hassan Yousef.

Hamas military guys began to hang around me just to show off. And because they thought I knew all the secrets of the organization, they felt comfortable sharing their problems and frustrations with me, believing I could help them with their issues.

I listened carefully. They had no idea they were giving me little bits of information that I was piecing together to create much bigger pictures. These snapshots led to more Shin Bet operations than I could describe to you in a single book. What I will tell you is that many innocent lives were saved as a result of those conversations. There were many fewer grieving widows and shattered orphans at gravesides because of the suicide bombings we were able to prevent.

At the same time, I gained trust and respect within the military wing and became the go-to Hamas guy for other Palestinian factions as well. I was the person they expected to provide them with explosives and to coordinate operations with Hamas.

One day, Ahmad al-Faransi, an aide to Marwan Barghouti, asked me to get him some explosives for several suicide bombers from Jenin. I told him I would, and I began to play the game—stalling until I could uncover the bombers’ cells in the West Bank. Games like that were very dangerous. But I knew I was covered from several directions. Just as being the eldest son of Sheikh Hassan Yousef kept me safe from Hamas-on-Hamas torture in prison, it also protected me when I worked among terrorists. My job with USAID gave me a certain amount of protection and freedom as well. And the Shin Bet always had my back.

Any mistake, however, could have cost me my life, and the Palestinian Authority was always a threat. The PA had some fairly sophisticated electronic eavesdropping gear that had been provided by the CIA. Sometimes they used it to ferret out terrorists. Other times it was deployed to root out collaborators. So I had to be very careful, especially of falling into the hands of the PA, since I knew more about how the Shin Bet operated than any other agent.

Because I had become the only point of access to my father, I was in direct contact with every Hamas leader in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Syria. The only other guy with that level of access was Khalid Meshaal in Damascus. Meshaal was born in the West Bank, but he lived most of his life in other Arab countries. He joined the Muslim Brotherhood in Kuwait and studied physics at Kuwait University. After Hamas was founded, Meshaal headed up the Kuwaiti chapter. And following the Iraqi invasion, he moved to Jordan, then to Qatar, and finally to Syria.

Living in Damascus, he was not subject to the travel restrictions of Hamas leaders in the territories. So he turned into a kind of diplomat, representing Hamas in Cairo, Moscow, and the Arab League. As he traveled, he raised money. In April 2006 alone, he collected one hundred million dollars from Iran and Qatar.

Meshaal didn’t make many public appearances; he lived in secret places, and he could not return to the occupied territories for fear of assassination. He had good reason to be careful.

In 1997, when Meshaal had still been in Jordan, a couple of Israeli intelligence agents broke into his room and injected a rare poison into his ear while he slept. His bodyguards spotted the agents leaving the building, and one of them went to check on Meshaal. He saw no blood, but his leader was down on the ground and unable to speak. The bodyguards ran after the Israeli agents, one of whom fell into an open drain. The agents were captured by Jordanian police.

Israel had recently signed a peace agreement with Jordan and exchanged ambassadors, and now the botched attack jeopardized that new diplomatic arrangement. And Hamas was embarrassed that one of their key leaders could be reached so easily. The story had been humiliating to all the parties involved, and thus everybody tried to cover it up. But somehow the international media found out.

Demonstrations broke out in the streets of Jordan, and King Hussein demanded that Israel release Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, Hamas’s spiritual leader, and other Palestinian prisoners in exchange for the red-faced Mossad agents. In addition, Mossad was to send a medical team immediately to inject Meshaal with an antidote to the poison. Reluctantly, Israel agreed.

Khalid Meshaal called me at least once a week. Other times, he left very important meetings to take my phone calls. One day, Mossad called the Shin Bet.

“We have a very dangerous person from Ramallah who talks to Khalid Meshaal every week, and we can’t find out who he is!”

They were referring to me, of course. We all had a good laugh, and the Shin Bet chose to keep the Mossad guessing about me. It seems there is competition and rivalry between security agencies in every country—as with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Central Intelligence Agency, and National Security Agency in the United States.

One day, I decided to take advantage of my relationship with Meshaal. I told him I had very important information that I could not give him over the phone.

“Do you have a secure way to deliver it?” he asked.

“Of course. I will call you in a week and give you the details.”

The normal means of communication between the territories and Damascus was to send a letter with someone who had no police record and no known relationship with Hamas. Such letters were written on very thin paper, rolled down to a tiny size, and then slipped into an empty medicine capsule or simply wrapped with nylon thread. Just before crossing the border, the courier swallowed the capsule, then regurgitated it in a restroom on the other side. Sometimes, a courier would have to carry as many as fifty letters at once. Naturally, these “mules” had no idea what the letters contained.

I decided to do something different and open a new secret channel to outside leadership, thus extending my access from the personal level to the operational and security levels.

The Shin Bet loved the idea.

I chose a local Hamas member and told him to meet me at my old cemetery in the middle of the night. To impress him, I showed up carrying my M16.

“I want you to carry out a very important mission,” I told him.

Clearly terrified yet excited, he hung on to every word from the son of Hassan Yousef.

“You can tell no one—not your family, not even your local Hamas leader. By the way, who is your leader?”

I asked him to write out his entire history in Hamas, everything he knew, before I would tell him more about his mission. He couldn’t get everything down on paper fast enough. And I couldn’t believe the amount of information he gave me, including updates on every movement in his area.

We met a second time, and I told him he was being sent out of Palestine.

“Do exactly what I tell you,” I warned, “and don’t ask questions.”

I told Loai that the guy was involved in Hamas up to his neck, so if the organization decided to check him out, they would find a very active and loyal member. The Shin Bet did its own vetting, approved him, and opened the border for him.

I wrote a letter

, telling Khalid Meshaal that I had all the keys to the West Bank and he could totally rely on me for special and complicated missions that he could not entrust to normal Hamas channels. I told him I was ready for his orders, and I guaranteed success.

My timing was perfect, since Israel had assassinated or arrested most of the Hamas leaders and activists by that time. Al-Qassam Brigades was exhausted, and Meshaal was desperately low on human resources.

I did not, however, instruct the courier to swallow the letter. I had designed a more complicated mission, mostly because it was more fun. I was discovering that I loved this spy stuff, especially with Israeli intelligence paving the way.

We bought the courier some very nice clothes—a complete outfit, so that his attention would not be drawn to the shoes in which, unknown to him, we had hidden the letter.

He put on the clothes, and I gave him enough money for the trip and a little extra to have some fun in Syria. I told him his contacts would recognize him only by his shoes, so he had to keep them on. Otherwise, they would think he was someone else and he would be in serious danger.

After the courier arrived in Syria, I called Meshaal and told him to expect to be contacted soon. If anyone else had told him that, Khalid would have immediately become suspicious and refused a meeting. But this man had been sent by his young friend, the son of Hassan Yousef. So he believed he had nothing to worry about.

When they met, Khalid requested the letter.

“What letter?” our courier asked. He didn’t know he was supposed to have a letter.

I had given Khalid a hint about where to look, and they found the compartment in one of the shoes. In this way, a new communications channel was established with Damascus, even though Meshaal had no idea that he was actually on a party line with the Shin Bet listening in.

Chapter Twenty

TORN

Summer 2001

Son of Hamas

Son of Hamas