- Home

- Mosab Hassan Yousef

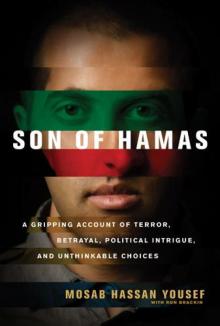

Son of Hamas Page 9

Son of Hamas Read online

Page 9

Finally, all of us except my cousin were sent to Megiddo. But this time we were not going to be on the side with the birds; we were headed to a real prison. And nothing would ever be the same again.

Chapter Twelve

NUMBER 823

1996

They could smell us coming.

Our hair and beards were long after three months without scissors or razor. Our clothes were filthy. It took about two weeks to get rid of the stink of the detention center. Scrubbing didn’t work. It just had to wear off.

Most of the prisoners started their sentence in the mi’var, a unit where everyone was processed before being moved to the larger camp population. Some prisoners, however, were considered too dangerous to be in the general population and lived in the mi’var for years. These men, not surprisingly, were all affiliated with Hamas. Some of the guys recognized me and came over to welcome us.

As Sheikh Hassan’s son, I was used to being recognized wherever I went. If he was the king, I was the prince—the heir apparent. And I was treated as such.

“We heard you were here a month ago. Your uncle is here. He will come to visit you soon.”

Lunch was hot and filling, although not quite as tasty as what I had eaten when I was with the birds. Still, I was happy. Even though I was in prison, I actually felt free. When I had time alone, I wondered about the Shin Bet. I had promised to work with them, but they hadn’t told me anything. They never explained how we would communicate or what it would mean to actually work together. They just left me on my own with no tips on how to behave. I was totally lost. I didn’t know who I was anymore. I wondered if maybe I had been scammed.

The mi’var was divided into two big dorms—Room Eight and Room Nine—lined with bunks. The dorms formed an L and housed twenty prisoners each. In the angle of the L, there was an exercise yard with a painted concrete floor and a broken-down Ping-Pong table that had been donated by the Red Cross. We were let out for exercise twice a day.

My bed was at the far end of Room Nine, right by the bathroom. We shared two toilets and two showers. Each toilet was just a hole in the floor over which we stood or squatted, and then we doused ourselves with water from a bucket when we were finished. It was hot and humid, and it smelled horrible.

In fact, the entire dorm was that way. Guys were sick and coughing; some never bothered to shower. Everybody had foul breath. Cigarette smoke overwhelmed the weak fan. And there were no windows for ventilation.

We were awakened every morning at four so we could get ready for predawn prayer. We waited in line with our towels, looking the way men look first thing in the morning and smelling the way men smell when there are no fans or ventilation. Then it was time for wudu. To begin the Islamic ritual of purification, we washed our hands up to the wrist, rinsed our mouths, and sniffed water into our nostrils. We scrubbed our faces with both hands from forehead to chin and ear to ear, washed our arms up to our elbows, and wiped our heads from the forehead to the back of the neck once with a wet hand. Finally, we wet our fingers and wiped our ears inside and out, wiped around our necks, and washed both feet up to the ankles. Then we repeated the whole process two more times.

At 4:30, when everybody was finished, the imam—a big, tough guy with a huge beard—chanted the adhan. Then he read Al-Fatihah (the opening sura, or passage, from the Qur’an), and we went through four rakats (repetitions of prayers and standing, kneeling, and bowing postures).

Most of us prisoners were Muslims affiliated with Hamas or Islamic Jihad, so this was our regular routine anyway. But even those who were members of the secular and communist organizations had to get up at the same time, even though they didn’t pray. And they were not happy about it.

One guy was about halfway through a fifteen-year sentence. He was sick of the whole Islamic routine, and it took forever to get him up in the morning. Some of the prisoners poked him, punched him, and yelled, “Wake up!” Finally, they had to pour water on his head. I felt sorry for him. All the purifying, praying, and reading took about an hour. Then everybody went back to bed. No talking. Quiet time.

I always had difficulty falling back to sleep, and usually I didn’t doze off until it was close to seven. By the time I was finally asleep again, somebody would shout, “Adad! Adad! [Number! Number!]” a warning that it was time to prepare for head count.

We sat on our bunks with our backs turned to the Israeli soldier who counted us, because he was unarmed. It took him only five minutes, and then we were allowed to go back to sleep.

“Jalsa! Jalsa!” the emir yelled at 8:30. It was time for the twice-daily organizational meetings held by Hamas and Islamic Jihad. Heaven forbid they should let anybody sleep for a couple of hours straight. It got really annoying. Again, the line formed for the toilets so that everybody would be ready for the nine o’clock jalsa.

During the first Hamas jalsa of the day, we studied the rules for reading the Qur’an. I had learned all of this from my father, but most prisoners did not know any of it. The second daily jalsa was more about Hamas, our own discipline inside the prison, announcements of new arrivals, and news about what was going on outside. No secrets, no plans, just general news.

After each jalsa, we often passed the time by watching television on the set at the far end of the room, opposite the toilets. One morning, I was watching a cartoon when a commercial came on.

BANG!

A big wooden board swung down in front of the screen.

I jumped and looked around.

“What just happened?!”

I realized that the board was attached to a heavy rope that hung from the ceiling. At the side of the room, a prisoner held tightly to the end of the rope. His job, apparently, was to watch for anything impure and drop the screen in front of the TV to protect us.

“Why did you drop the board?” I asked.

“Your own protection,” the man said gruffly.

“Protection? From what?”

“The girl in the commercial,” explained the board banger. “She was not wearing a head scarf.”

I turned to the emir. “Is he serious about this?”

“Yes, of course he is,” the emir said.

“But we all have TVs in our homes, and we don’t do this there. Why do it here?”

“Being in prison presents unusual challenges,” he explained. “We don’t have women. And things they show on television can cause problems for prisoners and lead to relationships between them that we don’t want. So this is the rule, and this is how we see it.”

Of course, not everybody saw it the same way. What we were allowed to watch depended a lot on who held the rope. If the guy was from Hebron, he would drop the board to cover even a female cartoon character without a scarf; if he was from liberal Ramallah, we got to see a lot more. We were supposed to take turns holding the rope, but I refused to touch the stupid thing.

After lunch was noontime prayer, followed by another quiet time. Most of the prisoners took a nap during this time. I usually read a book. And in the evening, we were allowed into the exercise area for a little walk or to hang out and talk.

Life in prison was pretty boring for Hamas guys. We were not allowed to play cards. We were supposed to limit our reading to the Qur’an or Islamic books. The other factions were allowed a lot more freedom than we were.

My cousin, Yousef, finally showed up one afternoon, and I was so happy to see him. The Israelis let us have some clippers, and we shaved his head to help get rid of the detention center smell.

Yousef was not Hamas; he was a socialist. He didn’t believe in Allah, but he didn’t disbelieve in God. That made him a close enough fit to be assigned to the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine. The DFLP fought for a Palestinian state, as opposed to Hamas and Islamic Jihad, which fought for an Islamic state.

A few days after Yousef’s arrival, my uncle, Ibrahim Abu Salem, came to visit. He had been under administrative detention for two years, though no official charges had ever been brought aga

inst him. And because he was a danger to the security of Israel, he would be there a long time. As a Hamas VIP, my uncle Ibrahim was allowed to travel freely between the mi’var and the actual prison camp and from one camp section to another. So he came to the mi’var to check on his nephew, make sure I was okay, and bring me some clothes—a gesture of concern that seemed out of character for the man who had beaten me and abandoned our family when my father was in prison.

At nearly six feet tall, Ibrahim Abu Salem was larger than life. His ponderous belly—evidence of his passion for food—made him appear to be some sort of jolly gourmet. But I knew better. My uncle Ibrahim was a mean, selfish man, a liar and a hypocrite—the exact opposite of my father.

Yet inside the walls of Megiddo, my uncle Ibrahim was treated like a king. All the prisoners respected him, no matter what faction they were with—for his age, his teaching ability, his work in the universities, and his political and academic accomplishments. Usually, the leaders would take advantage of his visit and ask him to give a lecture.

Everyone liked to listen to Ibrahim when he taught. Rather than lecturing, he was more like an entertainer. He liked to make people laugh, and when he taught about Islam, he presented it using simple language that everyone could understand.

On this day, however, no one was laughing. Instead, all of the prisoners sat in wide-eyed silence as Ibrahim spoke fiercely about collaborators and how they deceived and embarrassed their families and were the enemy of the Palestinian people. From the way he was speaking, I got the feeling he was saying to me, “If you have something that you haven’t told me, Mosab, you had better tell me now.”

Of course, I didn’t. Even if Ibrahim was suspicious about my connection with the Shin Bet, he wouldn’t have dared to say so directly to the son of Sheikh Hassan Yousef.

“If you need anything,” he said before he left, “just let me know. I will try to get you placed close to me.”

It was the summer of 1996. Though I was only eighteen, I felt as if I had lived several lifetimes in just a few months. A couple of weeks after my uncle’s visit, a prisoner representative, or shaweesh, came into Room Nine and called out, “Eight twenty-three!” I looked up, surprised to hear my number. Then he called out three or four other numbers and told us to gather our belongings.

As we stepped out of the mi’var into the desert, the heat hit me like dragon’s breath and made me light-headed for a moment. Stretched ahead of us for as far as I could see was nothing but the tops of big brown tents. We marched past the first section, second section, third section. Hundreds of prisoners ran to the high chain-link fence to see the new arrivals. We arrived at Section Five, and the gates swung open. More than fifty people crowded around us, hugged us, and shook our hands.

We were taken to an administration tent and again asked our organizational affiliations. Then I was led to the Hamas tent, where the emir received me and shook my hand.

“Welcome,” he said. “Good to see you. We are very proud of you. We’ll prepare a bed for you soon and give you some towels and other things you need.” Then he added with typical prison humor, “Just make yourself comfortable and enjoy your stay.”

Every section of the prison had twelve tents. Each tent housed twenty beds and footlockers. Maximum section capacity: 240 prisoners. Picture a rectangular picture frame, bordered with razor wire. Section Five was divided into quarters. A wall, topped with razor wire, bisected the section from north to south, and a low fence bisected it from east to west.

Quadrants One and Two (upper right and left) housed three Hamas tents each. Quadrant Three (lower right) had four tents—one each for Hamas, Fatah, the combined DFLP/PFLP, and Islamic Jihad. And Quadrant Four (lower left) had two tents, one for Fatah and one for the DFLP/PFLP.

Quadrant Four also had the kitchen, toilets, showers, an area for the shaweesh and kitchen workers, and basins for wudu. We lined up in rows for prayer in an open area in Quadrant Two. And, of course, there were guard towers at every corner. The main gate to Section Five was in the fence between Quadrants Three and Four.

One more detail: The fence running east and west had gates between Quadrants One and Three and between Two and Four. They were left open during most of the day, except during head counts. Then they were closed so officials could isolate half a section at a time.

I was assigned to the Hamas tent in the upper corner of Quadrant One, third bunk on the right. After the first head count, we were all sitting around talking when a distant voice shouted, “Bareed ya mujahideen! Bareed! [Mail from the freedom fighters! Mail!].”

It was the sawa’ed in the next section, giving everyone a heads up. The sawa’ed were agents for the Hamas security wing inside the prison, who distributed messages from one section to another. The name came from the Arabic words meaning “throwing arms.”

At the call, a couple of guys ran out of their tents, held out their hands, and looked toward the sky. As if on cue, a ball seemed to fall out of nowhere into their waiting hands. This was how Hamas leaders in our section received encoded orders or information from leaders in other sections. Every Palestinian organization in the prison used this method of communication. Each had its own code name, so that when the warning was shouted, the appropriate “catchers” knew to run into the drop zone.

The balls were made of bread that had been softened with water. The message was inserted and then the dough was rolled into a ball about the size of a softball, dried, and hardened. Naturally, only the best pitchers and catchers were selected as “postmen.”

As quickly as the excitement started, it was over. Then it was time for lunch.

Chapter Thirteen

TRUST NO ONE

1996

After being held underground for so long, it was wonderful to see the sky. It seemed as though I hadn’t seen the stars for years. They were beautiful, despite the huge camp lights that dimmed their brightness. But stars meant it was time to head to our tents to prepare for head count and bed. And that was when things got really confusing for me.

My number was 823, and prisoners were billeted in numerical order. That meant I should have been placed in the Hamas tent in Quadrant Three. But that tent was full, so I had been assigned to the corner tent in Quadrant One.

When it came time for head count, however, I still had to stand in the appropriate place in Quadrant Three. That way, when the guard went down his list, he wouldn’t have to remember all the housekeeping adjustments that had been made to keep things tidy.

Every movement of the head count was choreographed.

Twenty-five soldiers, M16s at the ready, entered Quadrant One and then moved from tent to tent. We all stood facing the canvas, our backs to the troops. Nobody dared move for fear of being shot.

When they had finished there, the soldiers moved into Quadrant Two. After that, they closed both gates in the fence, so that no one from One or Two could slip into Three or Four to cover for a missing prisoner.

On my first night in Section Five, I noticed that a mysterious kind of shell game was taking place. When I first took my place in Three, a very sickly looking prisoner stood next to me. He looked horrible, almost as if he was about to die. His head was shaved; he was clearly exhausted. He never made eye contact. Who is this guy, and what happened to him? I wondered.

When the soldiers finished the head count in One and moved on to Two, somebody grabbed the guy, dragged him out of the tent, and another prisoner took his place next to me. I learned later that a small opening had been cut in the fence between One and Three so they could swap the prisoner with someone else.

Obviously, nobody wanted the soldiers to see the bald guy. But why?

That night, lying in my bed, I heard somebody moaning in the distance, somebody who was clearly in a lot of pain. It didn’t last long, however, and I quickly drifted off to sleep.

Morning always came too quickly, and before I knew it, we were being awakened for predawn prayer. Of the 240 prisoners in Section Five, 140 guys got up and stoo

d in line to use the six toilets—actually six holes with privacy barriers over a common pit. Eight basins for wudu. Thirty minutes.

Then we lined up in rows for prayer. The daily routine was pretty much the same as it had been in the mi’var. But now there were twelve times as many prisoners. And yet I was struck by how smoothly everything went, even with that many people. No one ever seemed to make a mistake. It was almost eerie.

Everybody seemed to be terrified. No one dared break a rule. No one dared stay a little too long at the toilet. No one dared make eye contact with a prisoner under investigation or with an Israeli soldier. No one ever stood too close to the fence.

It didn’t take long, though, before I began to understand. Flying under the radar of the prison authorities, Hamas was running its own show, and they were keeping score. Break a rule, and you got a red point. Collect enough red points, and you answered to the maj’d, the Hamas security wing—tough guys who didn’t smile and didn’t make jokes.

Most of the time, we didn’t even see the maj’d because they were busy collecting intelligence. The message balls thrown from one section to another were from them and for them.

One day, I was sitting on my bed when the maj’d came in and shouted, “Everybody evacuate this tent!” Nobody said a word. The tent was empty in seconds. They took a man inside the now-empty tent, closed the flap, and posted two guards. Somebody turned on the TV. Loud. Other guys started to sing and make noises.

I didn’t know what was going on inside the tent, but I had never heard a human being scream like that guy did. What could he have done to deserve that? I wondered. The torture went on for about thirty minutes. Then two maj’d brought him out and took him to another tent, where the interrogation began again.

Son of Hamas

Son of Hamas